Wetlands: Peace and Security

-

Aquaculture, fisheries and coastal agriculture

-

Atténuation & Adaptation au Changement Climatique

-

Climate and disaster risks

-

Coastal resilience

-

Coastal wetland conservation

-

Community resilience

-

Natural infrastructure solutions

-

Rivers and lakes

-

Wetland agriculture and fisheries

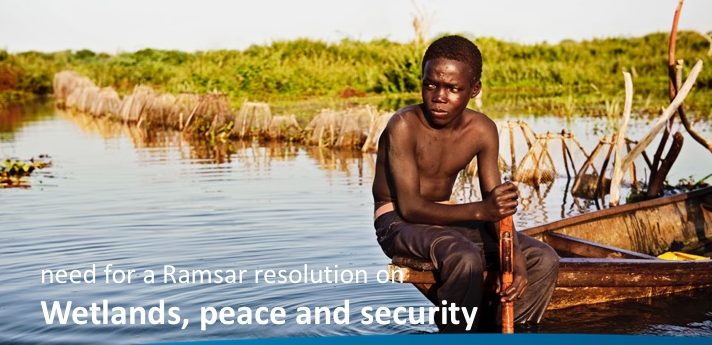

The number of conflicts worldwide has increased significantly over the past 10 years. This is displacing more and more people and increasing human insecurity. While many affected areas are centered around important wetlands, the relationship between wetlands, peace, and security is barely recognized. With security issues increasingly dominating the global agenda, it is time for a change.

While international organizations recognize the links between water, peace, and security, the role of wetlands remains largely unexplored. The Global High-Level Panel on Water and Peace, composed of 15 United Nations Member States, concluded last year that the global water challenge is not only a matter of development and human rights, but also of peace and security.

The Hague Declaration on Planetary Security in December 2017 highlighted climate risk as a key driver of human security and conflict. In a statement by the Secretary-General in January of this year, the United Nations International Security Council recognized that climate change and ecological changes are having negative effects on the stability of the Sahel region. It is time to integrate wetlands into the equation.

Healthy wetlands can make an important contribution to maintaining peace, while the loss of wetlands can contribute to growing insecurity. The Inner Niger Delta in Mali is a good example. I had the opportunity to discuss this with Soumana Timbo at an event organized by Wetlands International during an African conference on the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.

Timbo, Deputy National Director of Water and Forests and Ramsar Focal Point at the Ministry of Environment, Sanitation and Sustainable Development of Mali, explained how the ecosystem and economy of the Inner Niger Delta are linked to the annual flooding of its plains. “Any reduction in the floodplain translates into a significant negative impact through various conflicts,” he added. “The challenges are multiple because the inhabitants of the Inner Niger Delta often have different interests.”

The fewer resources there are, the more conflicts there are between the different users of the wetland resources: fishermen, farmers, and pastoralists. There are conflicts over access to the best fishing or grazing grounds, but there are also conflicts between different users: conflicts between farmers and herders, for example, because farmers do not consider access routes to watering points and pastures, and because herders must respect the agricultural calendar. In the Mopti region alone, there were already more than 500 conflicts related to pasture, agriculture, and fishing in 2016.

“The flooding patterns in the Inner Niger Delta have changed because flooding has changed due to natural circumstances such as climate change, but also due to the impact and management of new infrastructure upstream,” explains Timbo. “Rational and equitable management of the Delta’s ecosystems and improving the resilience of its communities will help to calm the social climate and reduce poverty among the population.”

Bongo and elephant in the Sangha wetland. Photo by Andrea Turkalo.

The state of wetlands impacts human security, and insecurity also impacts wetlands. An influx of refugees, for example, can affect the state of wetlands, and the protection and restoration of wetlands can be hampered by conflict. At the same Ramsar conference, I also met with Jules Tombet, a national expert in participatory forest resource management at the Ministry of Water, Forests, Hunting, and Fisheries of the Central African Republic (CAR). The situation he faces reflects an example of conflict affecting wetlands.

CAR has two protected wetland sites, Mbaere Bodingue and Rivière Sangha. Wetlands, consisting of rivers, marshes, lakes, and vast areas of dense forest that are periodically flooded, are responsible for flood control and prevention in the region. This ensures that the livelihoods of local communities are minimally affected during the rainy season.

Tombet explained that due to the conflict in CAR, these wetlands are affected by internally displaced people seeking shelter. “Between 1,000 and 3,000 displaced people have taken refuge in these wetlands, cutting down trees to build tents, thus contributing to deforestation and riverbank erosion. My plan is to work with the displaced people to restore these Ramsar sites while developing resilience activities,” he said, adding that 10 sites have been identified in the northern part of CAR bordering Chad. Given the still delicate security situation, only stability will allow their effective classification as Ramsar sites.

Mr. Jules Tombet, National Expert on Participatory Management of Forest Resources in the Ministry of Water, Forests, Hunting and Fisheries of the Central African Republic (RCA).

Wetland hotspots include both wetlands that contribute to insecurity and wetlands affected by conflict. These hotspots are not limited to Africa. The Mesopotamian marshes in Iraq and Iran, for example, are also affected by conflict. However, a comprehensive overview of wetland hotspots is lacking.

We do not claim that wetland degradation is the primary cause of insecurity and human conflict—natural resources and their management are almost never the sole cause of violent conflict. However, they can be significant drivers of conflict when they interact with various political, social, ethnic, and other factors. Wetland degradation and loss deserve much greater recognition and attention in relation to conflict and security.

In order to put the issue on the agenda of international organizations, we must first better understand the location and situation of wetland hotspots. Sometimes this can be sensitive, especially if A situation involves two or more countries, as is the case with the Mesopotamian Marshes. The Inner Niger Delta in Mali, the two protected wetlands in CAR, the Mesopotamian Marshes in Iraq and Iran, the Sudd in South Sudan, Lake Chad, and the Lorian Marsh in Kenya are definitely on our list. Feel free to add other examples and ideas in the comments!